“But people apparently are more likely to get agitated that way,” Merbitz says. Another contributor, she says, is a treatment strategy called “proning” in which patients are positioned on their stomachs to assist breathing and possibly prevent the need for a ventilator. While there’s been a trend in critical care medicine moving away from using large doses of sedating drugs with patients on ventilators, in an effort to reduce delirium, that’s also proven more difficult for several reasons, including that staffs are stretched thin with the influx of COVID-19 patients, Merbitz says. Since family members aren’t typically allowed to visit, they can’t practice the sort of family engagement that can be helpful, such as telling stories or reminding the patient that their favorite show is about to start, Hardin says. With clinicians wearing masks and other protective gear, it’s more difficult for them to connect with patients, she says. Patients treated for COVID-19 appear to be particularly vulnerable to delirium, likely due in large part that some prevention measures are less feasible amid the focus on reducing spread of the virus, says Abigail Hardin, PhD, a rehabilitation psychologist at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago. 9, 2017). A bundle of preventive measures to guard against delirium-an acute and fluctuating change in cognition and awareness-has been promoted for critically ill patients in recent years, with strategies that include less reliance on sedating drugs, earlier mobility and family engagement, among others. Intensive care unit patients already face a higher risk of delirium, with 20% to 40% of critically ill patients overall developing it and as many as 80% of those who required a mechanical ventilator, according to a review of delirium research (Pandharipande, P.P., et al., Intensive Care Medicine, Vol. There is no hopping over that.” Viral aftereffects And people are going to have to put together a sense of meaning and security as best they can. “There is inherent tragedy with this experience.

“Their world has been turned upside down,” Merbitz says. Ask open-ended questions and really listen as patients try to move beyond their scary encounter with the virus, she suggests.

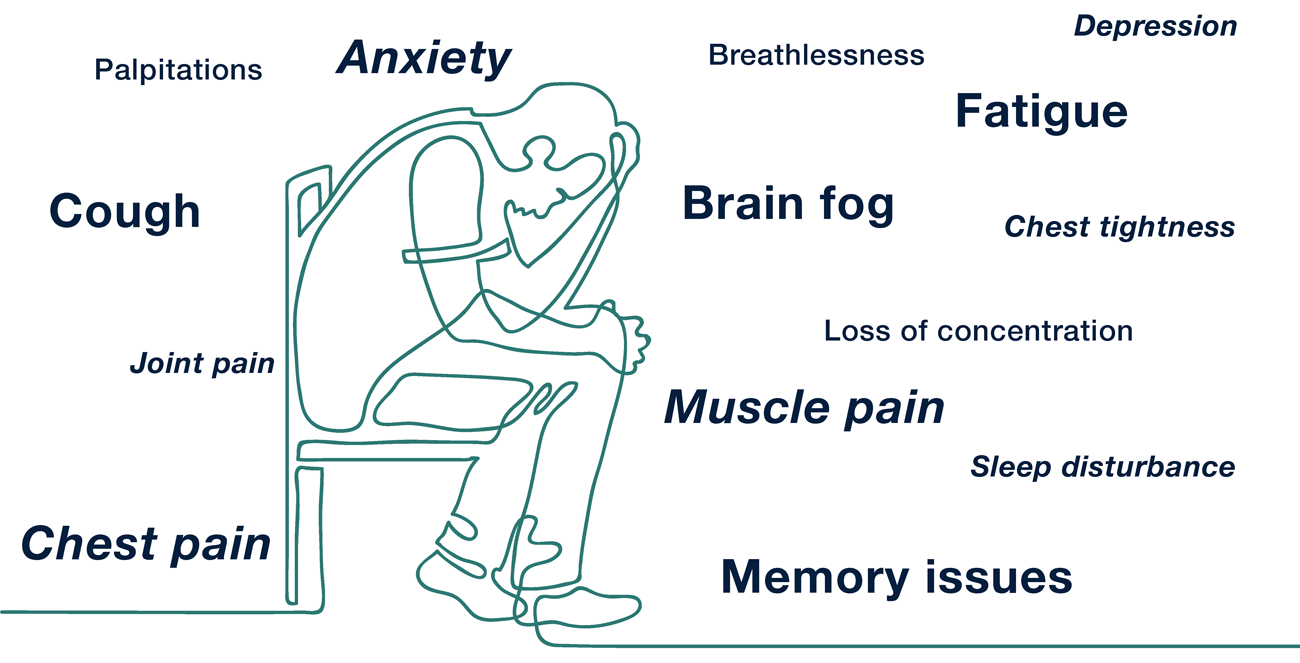

Psychologists also can assist patients with processing what they’ve been through, which may involve reconstructing gaps in their recollection, says Nancy Merbitz, PhD, a rehabilitation psychologist at the Lake County VA Outpatient Clinic in Ohio. That includes “teaching our patients early on in their recovery that there’s not going to be a medication fix,” she says, but that they can learn to adapt their approach to life to help overcome symptoms. “If we are going to effectively treat survivors, we need a comprehensive model for management,” Hosey says. “A lot of our survivors, even those who had what we would have considered mild to moderate symptoms, are describing things like fatigue, brain fog, sleep disturbance.” “Breathlessness won’t be the only symptom,” says Hosey, who also works with clinicians on the hospital’s Post-Acute COVID team. Prior research into Post Intensive Care Syndrome and acute respiratory distress syndrome can guide psychologists in their treatment, which may incorporate various strategies, from cognitive behavioral therapy to exposure therapy to breathing techniques, Hosey says. Psychologists fear that other challenges, such as survivor guilt, may flare once patients are discharged into a world still reeling from the virus.īut even though COVID-19 is a new disease, rehabilitation and health psychologists benefit from existing knowledge as they strive to help these patients, says Megan Hosey, PhD, an inpatient rehabilitation psychologist at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

Some difficulties, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, may be rooted in their experiences with hospital care and intensive care treatments. For patients who become seriously ill with COVID-19, survival may only mark the start of a complex recovery path.Īlong with potentially coping with cardiac, pulmonary and other physical effects, psychologists report that patients may have to sort through cognitive changes, such as difficulties with attention and memory, as well as mental health symptoms for months to come.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)